Tu carrito está vacío

If you hang around sword forums long enough, you’ll see steel grades tossed around like magic words. L6 cuts tatami like butter. T10 holds a scary edge. 9260 soaks up shock. There’s truth in those statements, but the full story is less about an alphabet soup of alloys and more about how the blade is engineered, heat‑treated, and finished. In other words, the label stamped on the billet is a starting point, not a verdict.

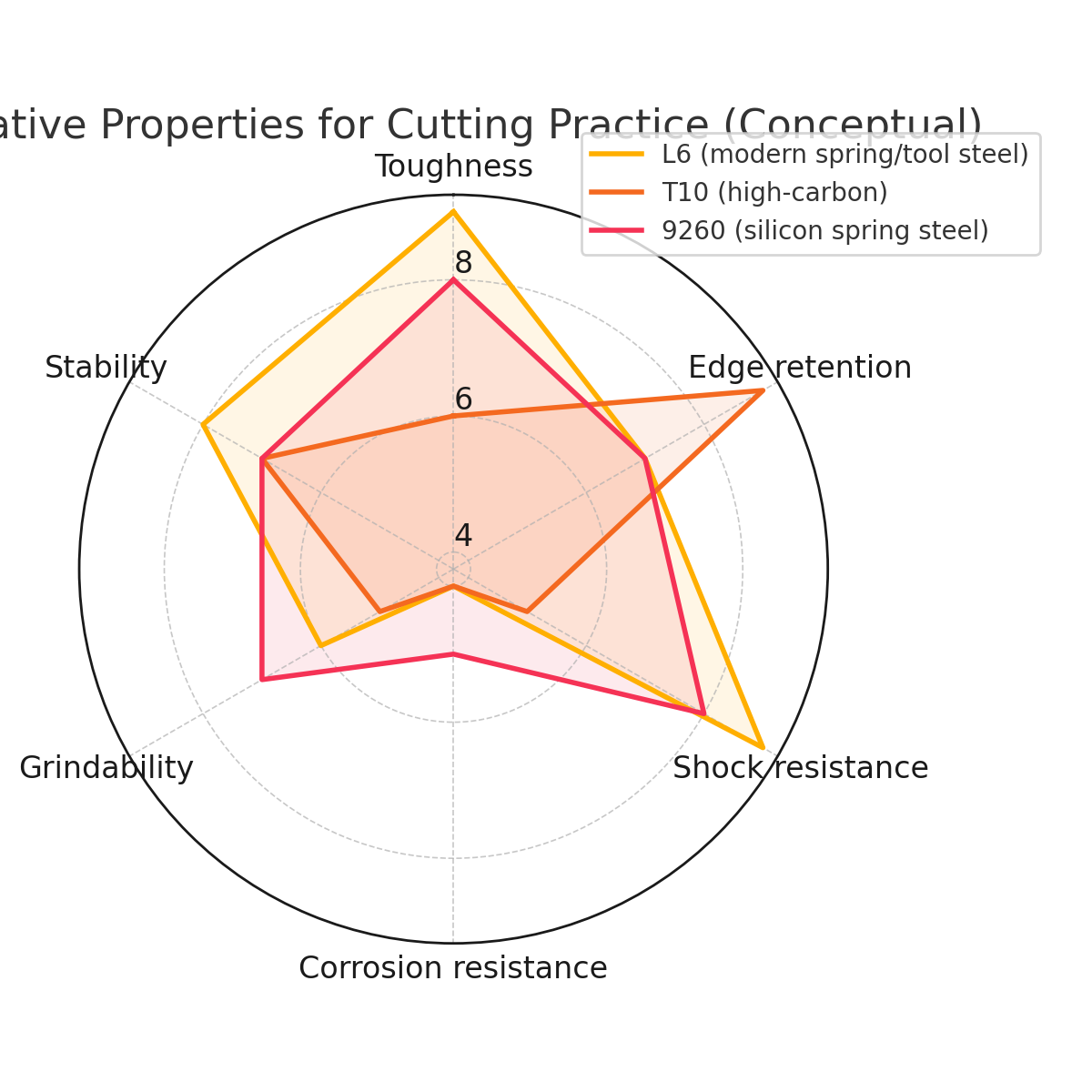

Let’s talk about what those labels really imply. L6 is a tough, modern alloy known for its resilience when it’s treated well; it’s often associated with spring‑like toughness and stability during hard use. T10 is a high‑carbon steel that can deliver excellent hardness and edge retention when managed carefully. 9260 is a silicon spring steel prized for shock resistance and forgiving behavior if your cutting technique isn’t perfect. If you read that and thought, “So L6 for bamboo, T10 for edge life, 9260 for training?”—you’re not wrong, but you’re only halfway there. Two blades with the same chemistry can behave very differently depending on the process behind them. A steel that looks legendary on paper can turn average in the hands of guesswork, and a humble spring steel can sing when the heat‑treat and geometry are dialed in.

Heat treatment is where the alloy’s promise becomes a blade’s personality. Temperature control, soak times, quenchant selection, temper cycles, and the smith’s intent decide where a blade lands on the hardness–toughness spectrum. A cutter geared for bamboo and dense targets usually biases toward toughness and a more conservative edge angle; a blade meant for soft tatami can be optimized to feel quicker through the cut with a thinner edge and a livelier balance. This is why two katanas from different shops—both marked L6 or both marked T10—can feel like different species in your hands. You’re not just buying a steel; you’re buying an approach.

Geometry quietly does as much heavy lifting as any metallurgical choice. The profile (shinogi‑zukuri, hira‑zukuri, etc.), niku (meat behind the edge), thickness tapers, and edge angle steer how a sword enters, tracks, and exits a target. A competition‑leaning geometry minimizes resistance in soft targets, giving you that “lightsaber” feel at the expense of margin on harder media. A traditional, more conservative geometry builds in insurance: slightly more niku, a less acute edge, and a bit more structural reserve for imperfect technique or ambitious targets. If you’ve ever felt a blade stall mid‑cut or steer off line, that wasn’t a steel label misbehaving—it was geometry and technique interacting under load.

Quality control and build consistency are the boring superpowers. Straightness, even heat‑treat across the length, a well‑seated tang, clean polish at the edge, and a properly wrapped handle are what make the steel and geometry show up reliably session after session. If you practice tameshigiri regularly, the sword you actually want is the one that behaves the same on your tenth cut as it did on your first.

So how do you translate all that to a buying decision? Start with your targets and your current technique. If you’re early in your cutting journey, a 9260 or a well‑treated L6 with moderate niku and a sensible edge angle will give you a wide safety margin and help you learn with fewer edge microchips from bad alignment. If you’re chasing feather‑light passes through soft tatami for competition, a carefully heat‑treated T10 or L6 with a leaner edge might give you the speed you crave—just respect the limits and keep your targets appropriate. If your dojo occasionally includes bamboo or heavier synthetics, favor toughness and geometry over marketing adjectives. Across all of these, prioritize the maker’s process and track record over the alloy’s mystique.

The takeaway is simple: steel matters, but only as part of a system. Think of cutting performance as the product of four factors—steel, heat treatment, geometry, and quality control. Change any one, and the character of the blade changes with it. Buy the system that fits your goals today and leaves room for your technique to grow.