Votre panier est vide

Traditional Japanese swords like the katana and uchigatana are synonymous with timeless style and superior quality. While other regions have produced swords using their own techniques, they generally pale in comparison to those produced in feudal Japan.

Japanese swords are widely recognized for their strength, which is the result of several factors, the most influential being high-carbon steel. Without high-carbon steel like tamahagane, swords produced in feudal Japan wouldn't have been nearly as strong. In order to produce this steel, however, swordsmiths would smelt iron and other metals in a large furnace known as a tatara.

How the Tatara Works

The traditional Japanese tatara differs from modern furnaces. While modern furnaces are usually cylindrical and made of metal, the tatara itself is actually a vessel made of hardened and solidified clay. Most importantly, though, the traditional Japanese tatara was a one-time use vessel. After it was used to produce high-carbon steel, it was smashed in an effort to retrieve the steel.

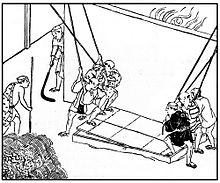

Most traditional tataras measured about 4 feet tall, 12 feet long and 4 feet wide. The tatara would be left to dry, after which it was heated by exposing it directly to an open flame. This smelter will then start a fire within the tatara using charcoal. And once the tatara has reached the desired temperature, iron sand known as satetsu is added. The smelter then adds an additional later of charcoal over the iron sand, repeating these steps several times over the next 72 hours.

Creating high-carbon steel using a tatara wasn't a quick or easy process. On the contrary, it took about a week to complete the process. Once the steel was ready, the tatara was smashed, allowing the smelter to retrieve the steel bloom ( kera). According to some reports, a traditional tatara that uses 10 tones of satesu and 12 tones of charcoal will yield roughly 2.5 tones of high-carbon steel.

Japanese Tataras Today

Around the early-to-mid 1900s, use of the tatara began to decline. It wasn't until the 1930s when it was ressurrected to mass-produce high-carbon steel for use in military swords. Of course, this was short-lived, as Japan stopped its military practices -- including sword production -- following the end of World War II. Fast forward to 1977, and the Japanese Society for Preservation of Japanese Art Swords (Nittoho) created a new tatara to produce swords. The new Nittoho tatara remains active, though it's only operational during the winter.